Desmond Carter is on a mission to save the lives of Black men.

Carter, founder of Mental Health Is Real Wealth, leads a bi-monthly mental health group in Los Angeles’ Leimert Park neighborhood, and on a recent Thursday, 15 Black men gathered inside a conference room without pressure and without women.

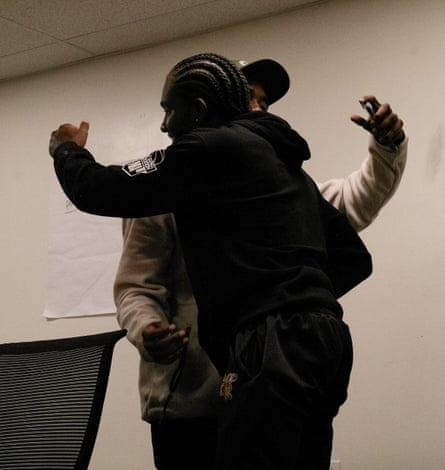

As the men walked in, they dapped each other up and leaned in for an embrace. Many wore LA paraphernalia – LA snapbacks, Crenshaw district street sign shirts and had various hairstyles – some had locs, fades and others had braids. The youngest man was 19 years old. There were several men who were more than twice his age. They were all there because they realized one thing: being vulnerable and taking care of your mental health is important.

Before they started their session, Carter, 37, told them of his best friend who died by suicide following a schizophrenic depression diagnosis. It’s a story he’s told multiple times.

“It happened literally 10 years ago, and it’s still tough,” Carter said, who remembers his friend as funny, fly and intelligent. But he often hid his diagnosis and would say he was OK. “It led me to do what I’m doing now. I see so many of my peers and people who look like me walking around, fly, cool, fresh with the weight of the world on their shoulders, and acting like they are just fine.”

The group is just one of the few Black male-founded safe spaces for men to fully let their guard down, and exists at a time when the suicide rates among Black boys and men have increased by 25.3% in recent years. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report that suicide is the third leading cause of death for Black male adolescents and young adults. Black boys and men make up an overwhelming majority of suicides within the Black population.

And right now, Black men exist between a rock and a hard place.

Before and after the peak of the Covid era, healthy spaces were limited for Black men to fully express themselves emotionally. Black men are less likely to seek mental health support. And even when they do, they are more likely to receive substandard culturally incompetent care which is rooted in racist health disparities , according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Research shows the Covid-19 pandemic increased loneliness and isolation amongst the general population. While there are public debates about the validity of a “male loneliness epidemic” and the impact of online misogyny in the “manosphere” in general, there’s one thing that’s underresearched and overlooked: Black men and their mental health.

Lance Lenford, a psychologist, said he noticed a shift in society during and after Covid. Gen X and millennial Americans were told that in order to reach the American Dream, they would have to go to school, get married and buy a house, but there’s now an identity crisis for those who have not been able to do so. This is especially true with Black men.

“I think that there’s this space where we’re figuring out how to be and how to exist in this – just to be frank – in this white world that we’re in while trying to spread our own wings and be who we feel we are meant to be, or who we can be …” Lenford said. “But you run into this wall, and you get to a point where it’s like, I don’t really know what I’m doing any more.”

For older Black men, there’s also an identity crisis as they start to think more about what retirement may look like for them and their ideal picture of what they want, not adding up. These issues are exacerbated once gen X and millennial Black men become fathers because of financial parenthood pressures.

While Black millennial men are now spending more time with their children than other groups and more than previous generations, when they are stressed, they may not have the time or money to go to therapy, Lenford said. There’s also the aspect of not having the chance to figure out your own identity before you’ve had a child.

“You have this duality of, ‘I have to be the provider,’” Lenford said. “I have to be this person that I want to be, and I believe that I am, and I presented myself to be, but I’m also kind of falling apart because I don’t really know where I’m going or how I’m really doing this.”

Black men’s significant challenges include economic, healthcare and educational disparities as well as systemic racism and social injustice, according to the American Psychological Association. Also, deaths of despair – deaths from suicide, alcohol use and drug overdoses are now higher among Black people than white people.

Along with the harms of living in a patriarchal society and having to subscribe to the roles of providers as men in general, the Black men in Carter’s group said they face specific pressures – to act tough, to already know how to do certain tasks, to be strong and not show emotions.

Some men were influenced to come to the meeting because another man told them to come. Others expressed being stressed, depressed or feeling like the world is caving in. They expressed the adjustment that comes from feeling like they are losing their masculinity or lifestyle and friendships due to the responsibilities of family life and parenthood.

“If I can do anything, if I look back and look at their lives and see that they didn’t do this, that they didn’t express themselves,” said one of the men, whose father and grandfather had history of bipolar disorder. “They were mad, and it took years, and then they just were more mad. And then something happened in their life, something flipped.”

Wayne Bennett, president of Mental Health is Wealth and a corporate wellness consultant and men’s life coach in Los Angeles, helps men build healthier ways to express their emotions whether it’s in a professional or personal sense. He said the group serves as a safe space for the men where they don’t have to wear a mask. His specific goal is to help men break generational cycles and foster emotional expression.

“A lot of the men talk about being depressed or not having any type of leadership growing up and just kind of having to figure things out on their own,” Bennett, 41, said. “A lot of the men may have never been to therapy before, so this is a great gateway to going into therapy.”

In LA, a region that has a unique history of police brutality , gangs and mass incarceration – all disproportionately affecting Black men, they have to wear a guard. Bennett said he had talked to Black men and they expect their interaction to be transactional, career-driven or aggressive. There is a lack of trust that men must build within each other in LA, he added.

Carter created the group in 2022 as a preventive measure to make Black men like him think about getting counseling and therapy. He said talking to other Black men has been healing for him, too.

“I just wanted this to be a space where they could kind of just dump, not only dump, but also celebrate wins as well,” he said. “I want this space for people and for our brothers to get their flowers.”

English (US)

English (US)