The strangest rumour started floating around just as the Beatles were breaking up – that I was dead. We had heard it long before, but suddenly, in that autumn of 1969, stirred up by a DJ in America, it took on a force all its own, so that millions of fans around the world believed I was actually gone.

At one point, I turned to my new wife and asked, “Linda, how can I possibly be dead?” She smiled as she held our new baby, Mary, as aware of the power of gossip and the absurdity of these ridiculous newspaper headlines as I was. But she did point out that we had beaten a hasty retreat from London to our remote farm up in Scotland, precisely to get away from the kind of malevolent talk that was bringing the Beatles down.

But now that over a half century has passed since those truly crazy times, I’m beginning to think that the rumours were more accurate than one might have thought at the time. In so many ways, I was dead … A 27-year-old about-to-become-ex-Beatle, drowning in a sea of legal and personal rows that were sapping my energy, in need of a complete life makeover. Would I ever be able to move on from what had been an amazing decade, I thought. Would I be able to surmount the crises that seemed to be exploding daily?

Three years earlier, I had bought this sheep farm in Scotland on the suggestion of one of my accountants. At the time, I wasn’t very keen on the idea – the land seemed sort of bare and rugged. But, exhausted by the business problems, and realising that if we were going to raise a family, it would not be under the magnifying glass that was London, we turned to each other and said, “We should just escape.”

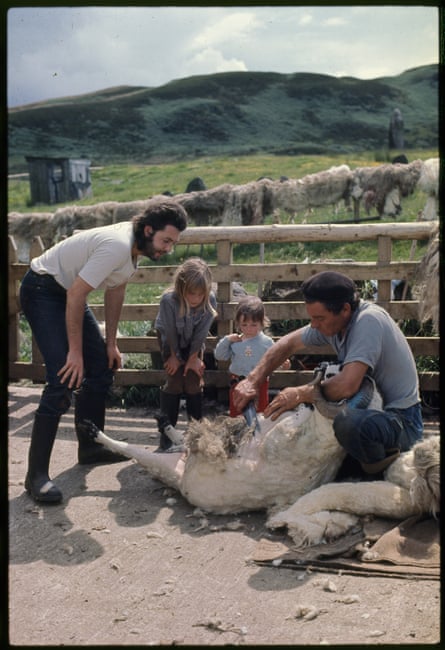

Looking back, we were totally unprepared for this wild adventure. There was so much we didn’t know. Linda would later go on to write famous cookbooks, but at first – and I’m a living witness – she was not a great cook. I was hardly any better suited for rural life. My father, Jim, still in Liverpool, had taught me many things, especially how to garden and love music, but putting down a cement floor was not one of them. Still, I wasn’t going to be deterred. So, I got a guy to come up from town who taught me how to mix cement, how to lay it down in sections, and how to tamp it to bring the water to the surface. No job seemed too small or too large, be it cutting down a Christmas tree from the local forest, making a new table, or getting on a ladder to paint an old roof. A big challenge was to shear the sheep. We had a guy called Duncan who taught me how to use old-fashioned shears and put a sheep on its haunches. Even though I could do only 10 sheep to his hundred, we were both knackered by the end of the day.

I took great satisfaction in learning how to do all these things, in doing a good job, in being self-dependent. When I think back on it, the isolation was just what we needed. Despite the harsh conditions, the Scottish setting gave me the time to create. It was becoming clear to our inner circle that something exciting was happening. The old Paul was no longer the new Paul. For the first time in years, I felt free, suddenly leading and directing my own life. Paul McCartney

Ted Widmer (editor of Wings: The Story of a Band on the Run, who pulled together the following quotes over two years, some from new interviews and some from archive tapes): High Park Farm was a 183-acre sheep farm on the Kintyre peninsula, in Argyllshire. In the autumn of 1969, Paul and Linda went there with their daughters Heather and Mary. It was a bleak time of year, but that may have added to the appeal, as Paul wrestled with depression.

One day, their privacy was breached by a writer and a photographer from Life magazine, wondering if Paul was still among the living. At first he was annoyed at the intrusion and was photographed throwing a bucket of slop at his unwelcome visitors. But then he realised it was better to give a thoughtful interview, even shaving for the photos. To settle the question, Paul explained his perspective on the Beatles and their impending demise. Remarkably, no one noticed when he admitted, “The Beatles thing is over.” But it was there in plain sight, when the interview was published, with Paul and his family on the cover. It would be a different story in a few months’ time.

Paul McCartney: The breakup hit like the atom bomb.

Klaus Voormann (musician): It was impossible. If you think of the last LPs – like Abbey Road, it’s a great record, it’s very professional, it has great songs, it’s well played, but the band didn’t exist any more.

Paul [in 1970]: You can’t blame John for falling in love with Yoko [Ono] any more than you can blame me for falling in love with Linda. We tried writing together a few more times, but I think we both decided it would be easier to work separately.

I told John on the phone that I was annoyed with him. I was jealous because of Yoko, and afraid about the breakup of a great musical partnership. It’d taken me a year to realise that they were in love.

Here’s my diary. September 1969. I was only 27. “This is the day that John said, ‘I want a divorce.’” The day the Beatles broke up. We decided to keep it a secret. I just remember thinking to myself, ‘Oh, fuck!’

Chris Welch (journalist): It’s a tragedy, really, that they broke up when they did. If they’d carried on, they would have had better management, better PA systems, and they could have done incredible shows. The Beatles at Glastonbury would have been amazing. But their time had come. They had to go.

Paul: Leaving the Beatles, or having the Beatles leave me, whichever way you look at it, was very difficult because that was my life’s job. So when it stopped, it was like, “Oh God, what do we do now?” In truth, I didn’t have any idea. There were two options: either don’t do music and think of something else, or do music and figure out how you’re going to do that.

Linda McCartney: I remember Paul saying, “Help me take some of this weight off my back.” And I said, “Weight? What weight? You guys are the princes of the world. You’re the Beatles.” But in truth, Paul was not in great shape; he was drinking a lot, playing a lot and, while surrounded by women and fans, not very happy. We all thought, “Oh, the Beatles and flower power” – but those guys had every parasite and vulture on their backs.

Mary McCartney: Mum and Dad just closed ranks. They were like, “We love each other. The only way to get through this is to get away from London, be really funky and just do the opposite of city life. Back to basics. Shearing sheep, picking potatoes, horse riding in the middle of nowhere, going to the beach with your kids, just being together. Sing, create music in your back room.”

Paul: We’d been plonked into this new life and we just had to figure it out.

Stella McCartney (born 1971): That American spirit that Mum had. Americans are a bit more positive, a bit more like, “Come on, chirp up.”

Paul: But all along, the person that didn’t go that way was Linda. She’s just that kind of woman, who could help me through that. Gradually we got it together.

Every year, the office had bought my Christmas tree. I remember thinking, “I’m going to go out and buy it myself.” With the Beatles, it had all been done for me. Once you realise that’s the way you’re living, you suddenly think, “Yes, come on! Come on, life, come on, nature!”

-

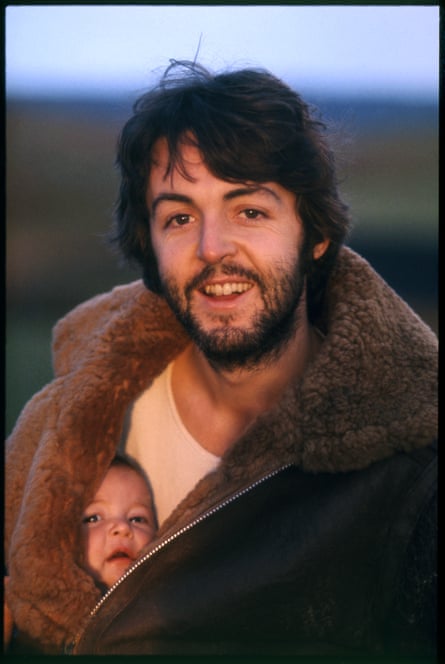

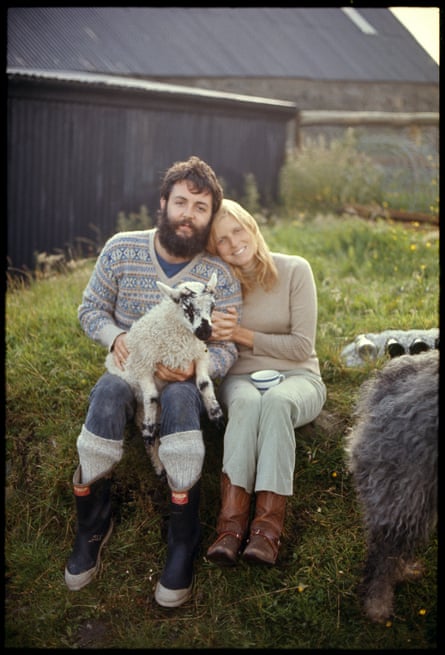

Paul with Mary, 1969 (left) and Linda, 1970 (right). © 1969, 1970 Paul McCartney under exclusive licence to MPL Archive LLP. Photographer: Linda McCartney

Stella: When I became a teenager, I hated going there. I was like, “Oh my God. This loch. This rock. Can I please just get to the Hamptons?” And now, honestly, they’re the best memories for all of us, that really unify and bring us all to the same place. Our family is so respectful to nature. It’s such a big part of who we are. And it was in its rawest form out there in Scotland, with the streams and the tadpoles. And you truly saw the seasons, and the flowers, and getting bucked off our horses, and having to walk through bracken. And the senses, you know?

Paul: We put our backs into it, tilling the fields, and grew all sorts in our vegetable garden. We had some seriously good turnips. I learned some tricks from my dad and his flowers in our garden at home, so put those to good use up in Scotland. And, to this day, it never ceases to amaze me: I put a seed in the ground, the rain comes to water it, the sun comes to shine on it, then something grows and you can eat it. That’s always something we can be grateful for.

We were back to nature – and the sky there is magnificent. There wasn’t much to spend our money on, and we didn’t have a lot of it then. But we were making do, and that was great, finding solutions to things. We didn’t have a bath. But next door to our little kitchen, there was a place where the farmers had cleaned the milking machinery. It was a tub that was 3ft off the ground, a big galvanised tub. I said, “We should fill this with hot water – we can have a bath.” It was that kind of thing.

-

‘No job seemed too small or too large. A big challenge was to shear the sheep’: McCartney is taught to clip sheep ‘by a guy called Duncan’, watched over by daughters Heather and Mary. © 1971 Paul McCartney under exclusive licence to MPL Archive LLP. Photographer: Linda McCartney

Mary: Mum and Dad would have the vegetable patch. Me and Stella would go down and sort of steal sweet peas and eat them there. I remember Dad liked peeling a bit of a turnip and saying, “Taste some of this. It’s the most delicious turnip you’ve ever tasted.” And we’d roll our eyes at him, going, “What the heck!” But now I’ve got to the age myself where I fully appreciate it. They went back to appreciating what you might call the simpler things in life, but I would say the more important things in life.

Stella: Scotland influenced so much. As children, it was the most peaceful place. The five of us – as James wasn’t quite born yet – were so isolated and we got to be a close-knit family. Mary and I bonded so much at that time because we were so close in age and we would horse-ride all day and get lost in the hills. For me, the fashion influence from that period was what was on the farm! Being on the road with Wings was rock’n’roll. It was just all so cool – sequins, velvets, rhinestones, platform boots, culottes, prints mashed up, airbrushing, graphic T-shirts. That style was just so iconic and the absolute contrast of Scotland, which was being in the fields and with family, in nature, and the sounds and the smells that came with that. All of the senses were completely on overload in Scotland because there was so much space and time around everything. You could really feel everything that was happening around you. On tour, everything was so chaotic. You went from a tour bus to a plane to the stage to your gig to backstage to whatever else. It was constant movement.

Paul: I ended up making a table, which was so gratifying. I’d taken woodwork in school. You ask most kids from that era, and woodwork was a favourite lesson. I decided I was going to do it with no nails, just with glue. I drew the thing, got my little sketches of how wide it was to be and how the legs were going to fit in. When I’d been in school, at the Liverpool Institute, we had woodwork classes, which a lot of us guys liked. I remembered a couple things, how to make a dovetail joint. I thought, “I know how to do that.” Over the next couple of months, I went into town and got myself a chisel and hammer. So, I had the whole structure, but it was still planks of wood, sitting in the corner of the kitchen. I didn’t dare try and put it together. But I bought some woodworking glue, Evo-Stik, supposed to be strong adhesive. One night, I just plucked up the courage and thought, “Here we go.” Right at the end, under the table, there was a cross-truss that had to fit in. And I suddenly thought, “Oh my God, it doesn’t fit.” But somehow I wangled it. I turned it upside down and then it fitted. I have an idea of how to do a thing, and then enough passion to follow it through. And the table’s still standing.

Chris Welch: Paul had two great allies when he returned from the Beatles and set off on his new musical career. One, of course, was Linda. And the other was the blank sheet of paper where he could write down all the ideas for new songs. They were the forces behind Paul then: blank paper and Linda.

-

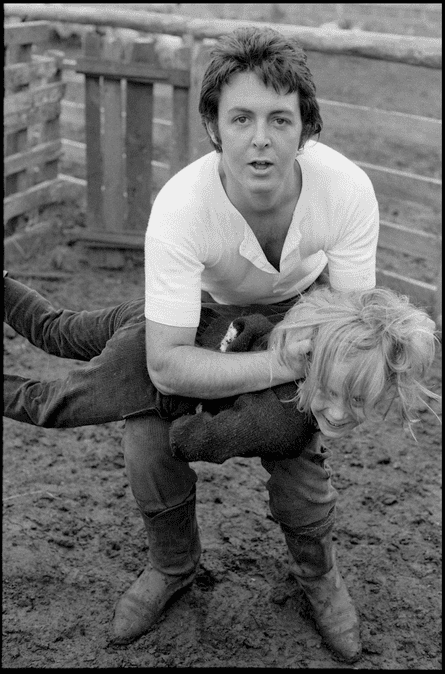

Paul plays with Heather in the mud (top) and a horse called Lucky Spot pokes its head through a window. © 1971, 1977 Paul McCartney under exclusive licence to MPL Archive LLP. Photographer: Linda McCartney

Paul: I hung on, wondering if the Beatles would ever come back together again, and hoping that John might come around and say, “All right, lads, I’m ready to go back to work.” In the meantime, I began to look for something to do. Sit me down with a guitar and let me go. That’s my job.

Michael McCartney (Paul’s younger brother): Loving your wife and then having children – there is another form of “Beatles”.

Chris Welch: It was Linda who encouraged him to come back, make some music, and later form a band, Wings. He did the best thing possible, which was to write songs about things that appealed to him, whether it was silly love songs or rock’n’roll. He wanted to experiment and be free to do what took his fancy. Things in everyday life. Cooking. Making breakfast.

Paul: Sometimes you manage just because you’ve got to. For me it was, “Well, I like music. What am I going to do?” So I got the four-track machine in the house and just started doing bits and pieces. I would sit around the house with a guitar. From that, I started writing; just making instrumental pieces. It’s something I still like to do to this day. That was how it started: just me in the living room at home, with the machine. I wasn’t trying to aim for popular success. I was just doing this because it was fun … It meant I hadn’t given up. It was some kind of continuum.

-

Paul with members of the Campbeltown Pipe Band who played on Wings’ 1977 single Mull of Kintyre. © 1977 MPL Communications Ltd

I didn’t really think it was going to be an album. It was just me recording for the sake of it. I’d get up and think about breakfast and then wander into the living room to do a track. The spirit of the times was, do it yourself, keep it simple, don’t get overblown. You’ve done the Beatles, you’ve done A Day in the Life, you’ve done Sgt Pepper. Now come back to basics.

For Maybe I’m Amazed [a song on his 1970 solo debut album, McCartney] I went into a studio. I was trying to put into words how it felt to be a young married person starting a life with this lovely girl, who I didn’t really know yet, but I was getting to know her. So there was a feeling of nervousness. Maybe I’m afraid of this thing? Which is true. The whole thing is scary when you fall in love with someone. There’s two sides. Yeah, it’s blissful. But then there’s also this scary side. So that’s what I was trying to do. I just put it together. Played the piano, drums, and the guitar solo, bass. Then we did some harmonies, and Linda was very good, her glee club training. We used to do that for fun around the house, singing like Patience and Prudence [two American sisters who formed a vocal duet that was active from 1956 until 1964]. We’d split off into these two parts. We’d work out how to do it. So Maybe I’m Amazed was me being amazed and afraid at the same time of being a grownup in a marriage for the first time ever.

This is an edited extract from Wings: The Story of a Band on the Run by Paul McCartney, edited by Ted Widmer, published by Allen Lane on 4 November. To support the Guardian, order your copy from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

Wings: The Definitive Self-Titled collection is out on 7 November on MPL/Capitol Records/UME.

English (US)

English (US)